Balancing New Technologies and Ease of Use in Infrastructure Cybersecurity Programs

The importance of cybersecurity in critical infrastructure was first recognized in the power industry with the creation of North American Electric Reliability Corporation Critical Infrastructure Protection (NERC CIP) standards. These requirements were developed in response to growing threats to the power grid and set a precedent for cybersecurity in other critical infrastructure sectors. Over the past two decades, various approaches have been taken to secure infrastructure, some of which were successful while others fell short.

While investing in the latest software solutions may appear to be the safest solution in the long run, there are limitations to this approach, most of which are related to limited resources and workforce constraints. These limitations carry clear risks and are at the center of a company’s decisions when deciding which technologies to invest in.

Real-life costs of a cybersecurity program

When evaluating the cost of cybersecurity technology, it is essential to consider more than just the upfront purchase cost. The lifecycle cost of this technology includes the overhead to support maintenance and operations, expenses for training and re-training workers, and the contracting of support for operations. Failure to consider these additional costs can result in unexpected operative expenses and reduced effectiveness of cybersecurity measures. For example, one common scenario is an organization that installed security features but has not used them, sometimes for years, because the employees trained to use them either retired or left the company. This scenario leads to increased security and compliance risks. To address compliance with new regulations many years ago, the industry took IT technology and injected it into non-IT environments without a proper way to evaluate outcomes or determine how easy it would be for the workforce to adopt these technologies.

Understanding the limitations of the talent pool

Critical infrastructure organizations, which rely heavily on operating technologies (OT), frequently face challenges in acquiring cybersecurity talent. As a result, critical infrastructure organizations often have to rely on upskilling existing internal resources to fill cybersecurity roles. While this approach can be practical, it is costly and sometimes unreliable. Unless the technology is simplified, it may not be a sustainable long-term solution, particularly given the ever-evolving nature of cybersecurity threats.

Project managers have wondered for years how to delegate these responsibilities to corporate IT departments. With their extensive knowledge of software tools, IT staff have the advantage of knowledge and experience. Their expertise, however, does not extend to OT processes. As a result, IT-managed programs face significant operational risks and may inadvertently increase the possibility of a cyber incident. For example, many OT organizations have relied on air-gapped systems for years, physically isolate OT resources from corporate networks. OT networks were kept safe using this principle, even when companies experienced incidents. Unfortunately, IT-managed programs require OT networks to be connected over the network to be managed remotely, eliminating one of the most valuable defenses to cyber-attacks.

Understanding risks

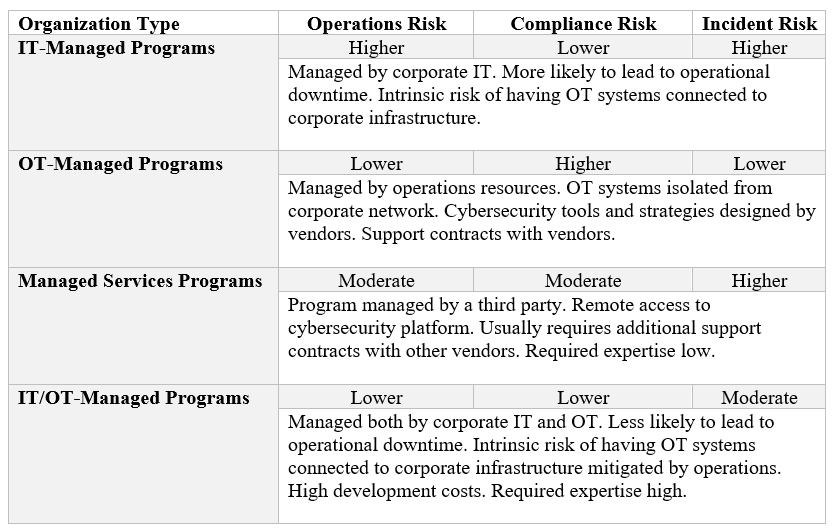

While risk management has evolved, it is not perfect. Organizations can now use their data points to estimate the likelihood of a cybersecurity event. There are three primary risks that need to be considered when estimating the cost of a cybersecurity program:

- Operational risk involves the risk of actions leading to downtime, which can result in lost revenue and failure to meet legal obligations. For example, assuming a price of electricity of 0.11 USD/kWh, a 400 MW generator suffering a 12-hour unplanned outage at a coal-fired plant could result in over $500,000 in lost revenue, plus any other contractual obligations.

- Compliance risk refers to the failure to meet cybersecurity regulations and resulting hefty fines.

- Incident risk refers to a successful breach or attack. The initial cost is, on average, over $4.82 million and may involve infrastructure damage and, in a worst-case scenario, the potential for loss of life.

Experience managing cybersecurity operations

Organizations typically choose among four widely accepted solutions for managing cybersecurity operations that seek to reduce risks: IT-managed programs, OT-managed programs, managed services programs, and IT/OT-managed programs. Each of these solutions has its own set of trade-offs (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Risks and rewards for various cybersecurity solutions

Historically, OT-managed organizations were popular with large utilities and IT-managed organizations were more popular with smaller utilities. The most important realization is these are all strategies to manage the complexity of the software. There is a need to simplify operations to the point where it is possible to mitigate human error, and more automation could be a solution. Surveys indicate that up to 95 percent of cyber incidents are caused by human error, therefore, moving fast is not always the best option.

Balancing new technologies with ease-of-use

Any change in software carries significant liabilities. A clear commonality is at the center of this problem: how easy will the software be to use, or, conversely, how likely it will be for people to make a mistake. Technically, implementing new software is affordable if the software is easy to use and the likelihood of making a mistake is very low. In addition to the power industry, other critical national infrastructure fields suffer similar implementation obstacles. That is one of the primary reasons why the current administration has prioritized developing new cybersecurity technologies for critical infrastructure and is investing accordingly.

How to move forward

OT programs work but are proving unsustainable as the workforce retires, organizations grow smaller, and new talent is hard to acquire. The solution for large organizations may be a joint IT/OT program. Consider these opportunities:

- Develop IT/OT programs in lower-risk facilities. A prime example in the power industry is renewables. Solar sites, for example, have fewer moving parts, require less maintenance, and worst-case scenarios are far less catastrophic than at a coal-fired power plant or nuclear facility. This type of program would help IT groups develop an understanding of OT infrastructure and converge to find better solutions and new standards that higher-risk facilities can implement.

- Even with better-managed programs and software, some critical infrastructure operations will continue to operate in isolation. For example, no efficiency metric can compensate the risk of a cyber incident at a nuclear facility. Even with this scenario, there is enormous value in solutions that are easier to use.

- Monitoring the cost of acquiring technically complex solutions will be essential and should be used in deciding what solutions to implement. Most corporate efforts focus on training, but there are limits to what that can achieve.

There is also an opportunity for new products, including:

- Easy-to-deploy solutions that integrate with IT platforms but are designed to be maintained by non-IT professionals.

- Third-party testing and certification of software features used in critical infrastructure. Knowing which configurations accomplish the desired outcome is a strong selling point that simplifies new implementations.

As these initiatives prove successful, they will likely be implemented in other industries that, while not necessarily categorized as critical infrastructure, suffer from rising cybersecurity costs and limited cybersecurity experts.

Juan Vargas

A graduate of Carnegie Mellon University, Juan Vargas started his career doing data analysis at Intel Corp before focusing on automation and control systems at Emerson Electric and finally becoming a cybersecurity expert for those systems. He has worked with most control systems in power generation and on various projects for all of the top 10-utility companies in the United States. Juan can be reached on Twitter @JuanVargasCMU.